Welcome to my series of blog posts Travels in Scotland. Whether you're planning a trip, reliving a memory, or relaxing into some armchair traveling...thank you for joining me! Here I will show you my images & share stories of my one month travels through Scotland. I'll cover this beautiful country of mountains, rivers, glens, islands, history, and, of course, fiber and textiles.

St. kilda

Soay sheep - a viking legacy

The feral Soay sheep on St. Kilda found on the main Island of Hirta, are descendants of Bronze Age Northern European short-tailed sheep brought to the island by the Vikings over 2, 000 years ago. The word "soay" is from the Scottish Gaelic and Old Norse words for "island of sheep."

These Soay, with their ancient unbroken genetic ancestry and isolation on a remote island, are the closest we have to a representation of sheep the way they were in Neolithic times. Soay measure in at about 1/3 the size of modern domesticated sheep. They are designated a primitive breed. Rather than being a derogatory term, primitive conveys highly adaptive traits such as disease-resistance, ability to live in harsh climates and ability to bear young on their own. In other words, the Soay are what sheep were like when humans began domesticating animals.

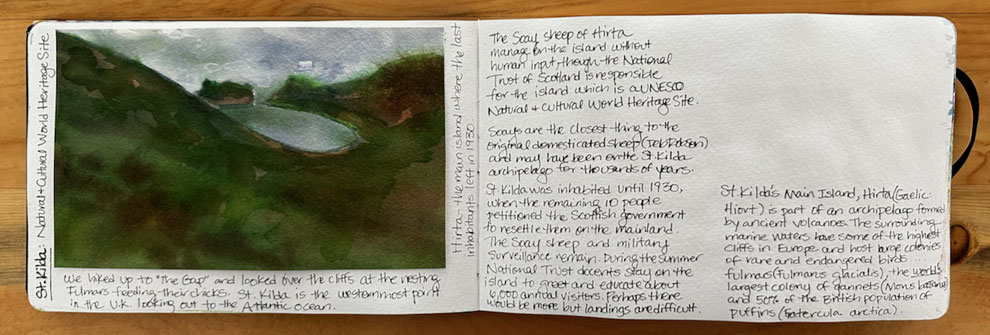

Since St. Kilda's last human colony left these islands almost 100 years ago, the flocks of St. Kilda have been wild, meaning that they live without human intervention. Soay have never needed to have their fleece shorn yearly, which is what domesticated sheep require, instead, Soay sheep molt their wool - naturally shedding and rubbing the wool from their coats - an adaptive ancient trait. (Note: Although there are no permanent residents on St. Kilda, the islands and flocks are monitored by the National Trust for Scotland and UK University Researchers.)

The Rare Breeds Survival Trust (RBST) lists Soay as "at risk" as a breed on the RBST Watchlist. There are numerous flocks of Soay apart from St. Kilda in the UK and 20 flocks in the North America. Efforts to conserve endangered breeds relies on not having all animals in one location (don't have all your eggs in one basket). Spinners, weavers, and makers all over the world can support farmers who are conserving rare and endangered breeds, by buying their wool products providing an income that sustains the keeping of rare breeds. In the United States, the Livestock Conservancy has a program called "Shave 'em to Save 'em" which puts fiber artists and producers in touch directly, benefitting both parties and supporting the conservation efforts.

But just how and why did the Vikings bring these sheep to St. Kilda so long ago? It is a story of women and the textiles they produced that powered the Viking age of course!

According to researchers at the Viking Ship Museum in Roskilde, Denmark, in the 11th century, at the Vikings zenith, the Viking fleet outfitted with woolen sails would have required the wool from 2 million sheep each year. The staggering number of sheep needed to provide wool for sails, does not count the wool for the clothing and domestic goods needed to survive the northern winters. Scandinavian countries have short growing seasons and limited arable land, so the choice must be to grow corn to feed the people and graze sheep for the wool sails, rather than to grow flax for linen sails that leaves little farmland left to grow food. The land needed to graze so many sheep, may explain the exportation of sheep to islands, like the Faroes, Iceland and St. Kilda, where no predators exist and the ocean serves as fences. The Vikings need for wool was greater than their available land could provide.

At the same time, consider the time and skill of the women who processed the raw wool of more than 2 million sheep annually, spun the fiber into thread and yarn, and then wove the sails, clothing and household items. Whereas a boat could be built by two men in two weeks, it took two women one year to turn sheep's wool into one sail. No wonder that Viking women were buried with their most prized possessions: spindle whorls.

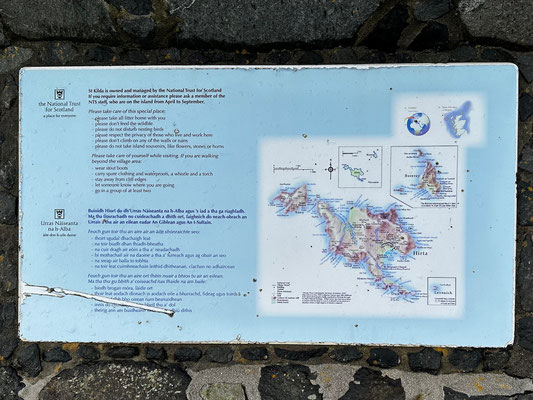

UNESCO WORLD HERITAGE SITE

Is there anything that can prepare a person for a visit to one of the most remote and inaccessible islands in the North Atlantic? St. Kilda is the furthest western island from the European continent and the last land when traveling from the UK to North America. A UNESCO Warden and a few military personnel are the last of the part-time inhabitants, along with about 5,000 yearly visitors. Many more visitors attempt the visit and are turned away because sitting alone out in the Atlantic Ocean means that weather and rough seas make landing a boat unpredictable. St. Kilda is for many, as it was for me, a "bucket list" destination. There is something magnetic about experiencing a place on the outer limits. Maybe it's an antidote for modern life. Maybe it's a drop of viking blood in us.

UNESCO has recognized the importance of St. Kilda. The islands have some of the highest cliffs and the largest seabird colonies on the islands in Europe, including Puffins, Fulmars, Gannets, Kittiwakes, Guillemots, Terns, Arctic Skuas, Shags, Gulls and Eiders. St. Kilda is without question a very special place. It was a privilege and a thrill to visit St. Kilda- a once in a lifetime experience.

Blog tip: Click on any photo to enlarge and read caption

There is a story about why the last humans left St. Kilda

Archeologists believe that St. Kilda has been inhabited since the Iron Age (2-3,000 years ago) and some believe even further back (4-5,000 years ago) having dated some of the stone structures on the islands to the Neolithic. There is a story about how it came to be that the last 36 people to live on St. Kilda, petitioned the Scottish government to be removed from the island in 1930, but it is complex, hard, and heartbreaking and I leave this storytelling to others, to tell you more about the place and the sheep. Linda Cortright of Wild Fibers Magazine has done a lot of research and writing on the topic. And there is some interesting historical movie footage from 1928 (start at 6:50) to watch to get a sense of what life was life in this remote, windswept part of the world.

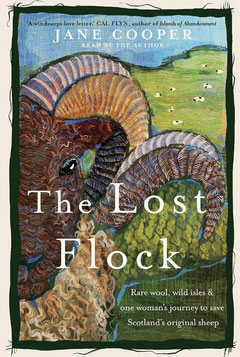

Boreray - the other island in the ST. Kilda chain and its sheep

The chain of St. Kilda contains four islands: Hirta (the main island where the Soay sheep live), Soay, Dun, and Boreray. And if the story of the Soay wasn't exciting enough, there is another ancient, primitive breed of sheep - the Borerary. Also listed by the Rare Breed Survival Trust as at risk, the Boreray are being raised and conserved on the Orkneys as chronicled by Jane Cooper in her new book, The Lost Flock (2023). I highly recommend this book to anyone interested in sheep and visiting Scotland.

Like the Soay, Boreray's wool naturally molts and can be roo'ed (hand plucked during molting time - think of your own hair the comes out when shampooing in the shower). For the readers interested in hand spinning, here is Freyalyn's blog.

If you like videos, here's Jane Cooper speaking about this book at the 2023 Orkney International Science Festival!

more sheep to come

The stories of the primitive breeds are about adaptation and survival. This reminds me of the origin of the humble potato. Potatoes were first cultivated by the Incas in the Andes 8,000 - 5,000 BCE, and instead of the 4 or 5 varieties we can buy in our grocery stores, the International Potato Center in Peru has archived 5,000 varieties of potatoes. Being in a harsh and changeable environment, the Incas sowed not one potato crop but dozens into the ground and their efforts yielded food no matter the soil or weather conditions.

I think that I worked with yarn for most of my life before I became aware that there were different breeds of sheep, just like having eaten potatoes my whole life thinking there was the type for baking and the type for mashing. Different breeds of sheep and their fleece have different properties that can be worked with different spinning methods to produce different types of yarn. Learning to handspin sheep's wool and learning about how commercial yarn differs from handspun, has certainly been an education in the diversity of sheep breeds and their wool. But, seeing in person the environment where a sheep breed originated and adapted to the challenges of that place, that adds one more dimension to the whole picture.

The total population of sheep in Scotland is about 6.8 million. So far on my journey, I've seen a few of the 1,000 sheep on the Isle of Iona and some of the 1,700 Soay sheep on Hirta, St. Kilda. Traveling around the Scottish Isles gives an opportunity to see different breeds of sheep, some modern, some primitive, all with their own place and stories. In the next few blog posts, more breeds, insights, and questions about wool and yarn are coming.

references

Weaver & Weaver (2021) Soay Sheep: Island survivors in today's world, Ply: The Magazine for Handspinners, Double-Coated Issue 32

Reid (2021) Spinning Soay: Ideal for life on a wet, windswept island, Ply: The Magazine for Handspinners, Double-Coated Issue 32

Robson & Ekarius (2011) The Fleece & Fiber Sourcebook, Storey Publishing

Fournier & Fournier (1995) In Sheep's Clothing: A Handspinner's Guide to Wool, Interweave Press, Inc.

Cooper (2023) The Lost Flock: Rare Wool, Wild Isles, and One Woman's Journey to Save Scotland's Original Sheep, Chelsea Green Publishing

Lightfoot (1996) The Story of a Woolen Sail, published in the Norwegian Textile Letter, Robbie LaFleur Publisher

Zawinski (2015) In the Footsteps of Sheep: Tales of a journey through Scotland walking, spinning and knitting socks, Schoolhouse Press

Coulthard (2020) A Short History of the World According to Sheep, Anima Publishing

Cortright (2009) Eviction at sea, Wild Fibers Magazine, Vol. 6, Issue 1

Eamer (2016) No Wool, No Vikings: The fleece that launched 1,000 ships, published in Hakai Magazine: Coastal Science and Communities

Ribe Viking Center Documentary (2019) The Weaver's Lesson in Sail Making

ARO42: Hirta, St. Kilda: Archaeological Investigations (2021) Archaeological Reports Online, Glasgow, Scotland.

UNESCO World Heritage Convention website

National Trust for Scotland St. Kilda dual conservation site

Soay and Boreray Sheep Society: Friends of the Sheep of St. Kilda

Wild Fibers Magazine and Tours with Linda Cortright

COMING UP IN TRAVELS IN SCOTLAND POST 6: seaweed-eating sheep

Thank you for reading my blog post. Travels in Scotland is a 12 part blog series filled with photos and stories of a fiber artist's journey through a beautiful country, encountering a land with a deep textile history, stunning landscapes, and of course sheep!

You can read all of the Travels in Scotland blog posts on my website. I invite you to travel along with me, along the coast and through the mainland hills seeing, experiencing and learning about this place called Scotland.Turas math dhuibh! (Good journey to you!) Amy

Write a comment

Andrew Fleming (Sunday, 16 February 2025 04:32)

If you would like a serious research-based update on the sheep of the st Kilda archipelago,

do feel free to get in touch - andrewfleming43@btinternet.com